A Sommelier’s Journey Through Alentejo Part 2

Sorry for having to break this post into two, but as you can tell, I visited too many good places to leave any behind.

Herdade do Rocim (Vidigueira)

Rocim felt like a dialogue rather than a statement.

Set in Vidigueira, the estate sits at a crossroads philosophically. Here, ancient talha traditions exist alongside modern winemaking with no sense of competition between them whatsoever. Neither is treated as novelty, and neither is asked to justify itself. They simply coexist, each sharpening the other and pushing each other to bring out the best of them.

The amphora wines spoke quietly but persistently, carrying texture and earth without heaviness. The more contemporary bottlings showed precision and freshness, resisting the assumption that Alentejo must always lead with bold power. What impressed me most wasn’t the contrast, but the coherence. There was a sense that every decision was made in give-and-take with the land rather than in reaction to trends.

Rocim challenged some of my deepest assumptions about inevitability in warm-climate regions as well. I’m so used to alcohol, ripeness, and weight coming with heat, but these wines show they’re choices here, not foregone conclusions. Tasting through the wines, I felt the same thing I had felt elsewhere in Alentejo, patience deeply, deeply embedded into process. At Rocim, that patience came with a willingness to ask how tradition can continue without becoming fixed.

It was like Alentejo thinking out loud.

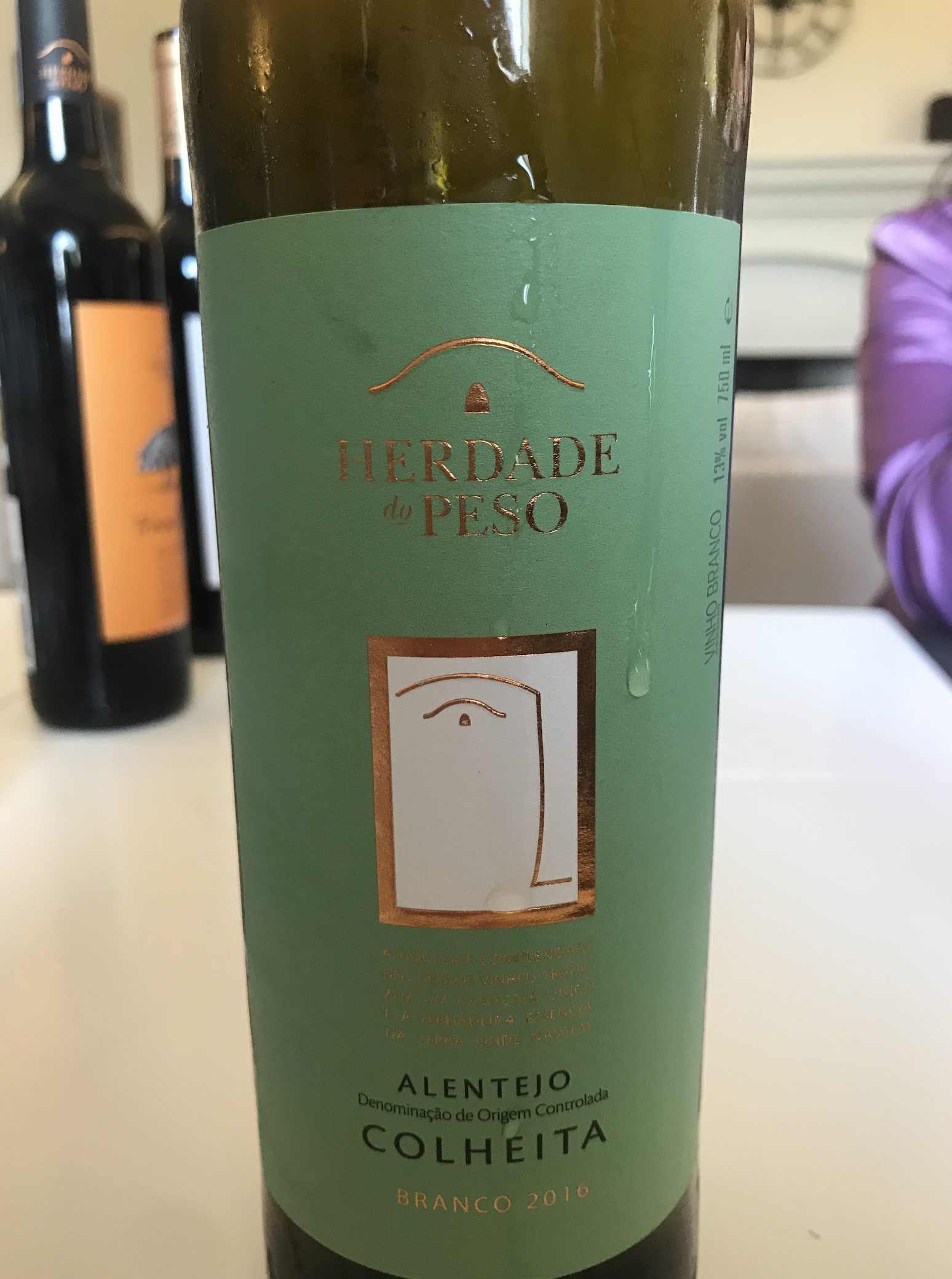

Herdade do Peso (Vidigueira)

Herdade do Peso reinforced how much micro-region still matters.

The winemaking here balances respect for Alentejo’s generosity with a desire for control. The wines felt composed, built to carry weight without becoming heavy, their whites were surprisingly lean and delicious. There was a confidence in how they held themselves, as though the winemakers trusted their understanding of the land enough not to overcorrect it.

Spending time with the wines, it became clear that Herdade do Peso isn’t interested in any sort of grand awards. The focus is consistency, balance, and expression, wines that speak honestly about Vidigueira without smoothing away its edges.

Paulo Laureano Wines (Vidigueira)

Paulo Laureano’s wines spoke plainly.

Often described as one of the architects of modern Alentejo, Laureano approaches winemaking with a scientist’s focus and a regionalist’s loyalty. His work has long centered on understanding what Alentejo’s native grapes are capable of when they are treated as individuals rather than blended into anonymity. As I mentioned in my previous post, I’m partial to native grapes because nature spent centuries and much longer fine-tuning these varietals.

The wines reflected that intent immediately. Varietal expressions were clear and unapologetic with Antão Vaz showing structure and grip rather than softness and Alicante Bouschet carrying depth without excess weight. These were not wines built to charm quickly, rather, they open and breathe in a glass, demanding presence and moments.

What stood out most at this winery was the precision. Nothing felt ornamental or inflated. Oak was measured, ripeness was intentional, each wine seemed to arrive at the table already knowing what it was meant to say, and saying only that.

Paulo Laureano’s wines felt like a statement of confidence, proof that Alentejo doesn’t need embellishment to be compelling. When handled with focus and restraint, the region speaks clearly enough on its own.

Bacalhôa – Quinta do Carmo (Estremoz)

Quinta do Carmo carried weight.

Set outside Estremoz, the estate feels shaped by accumulation rather than intention, literal centuries of viticulture layered quietly into the land. Nothing here feels rushed or newly decided, there’s a sense of ancientness to the world that makes you long for a time before social media and the internet. The vineyards, the buildings, even the air carry the sense that many choices have already been made, tested, and lived with over time.

The wines reflected that inheritance beautifully. They were structured, steady, and confident without theatricality. Balance felt truly earned rather than engineered. These were wines built with real memory, not chasing immediacy, not bending toward trends, but holding a line that had been drawn long before this moment.

Did I mention the hospitality in Portugal was absolutely insane? The winemaker opened some old bottles for us to enjoy, and I can confirm these age like the best Bordeaux wines.

What stayed with me was the sense of continuity throughout their wines. Quinta do Carmo didn’t feel like a place trying to define itself, it felt like a place that already knew who it was. Tasting there reminded me that the wines stop trying to explain themselves a long time ago, now they simply endure Father Time.

Arrepiado Velho (Estremoz)

Arrepiado mattered not just because of what was poured, but because of how time behaved there.

Lunch stretched in a way that felt intentional rather than indulgent. Courses arrived when conversation allowed for them, not when a clock demanded it. Wine moved quietly through the table, sometimes noticed, sometimes simply present, doing its work without asking to be discussed. However, of course, there were about four sommeliers at the table, so most of our conversation revolved around the wines.

This husband and wife team created works of art in their home, from the vines to the labels. The wife was an artist and designed all the labels herself. They were all deeply symbolic, yet also compelling. I’d recognize their design in any lineup of bottles around the world today. Their art was branded with more art.

What stayed with me here was the absence of urgency. No one seemed concerned with pace or productivity, and we were very late leaving here. The meal unfolded as if the afternoon belonged to it, and in Alentejo, that kind of confidence is its own philosophy.

Take this wine here as an example of the winemaking here, “Brett Edition” came about because the winemaker chose not to fight what most modern cellars try to erase. Instead of scrubbing the wine clean, they leaned into Brettanomyces in this wine, not as a flaw, but as part of the wine’s identity. Brettanomyces is a wild yeast that can appear during fermentation or aging, especially in lower-intervention wines. In excess, it can overwhelm a wine, which is why it’s considered a “fault”. But in slight restraint, it introduces savory, earthy notes like leather, dried herbs, or forest floor, characteristics once common in traditional European wines before technology made it possible to eliminate them entirely.

In this bottle, brett isn’t contamination, it’s a choice to preserve complexity, and a reminder that wine doesn’t always need to be clean to be true. That decision wasn’t careless, it was controlled, intentional, and confident. The result is a wine with tension and depth, something slightly feral at the edges, unwilling to flatten itself for easy approval.

Arrepiado wasn’t about instruction or impression, it was more about letting wine exist alongside food and people without being elevated or analyzed to death. In that way, it became one of the clearest lessons of my trip. Meaning doesn’t always come from intensity, sometimes it comes from staying long enough to stop checking the time.

Adega Monte Branco (Casa Branca)

Monte Branco felt quiet in a way that demanded attention.

Set near Estremoz, the vineyards sit on soils shaped by one of Portugal’s most defining materials: marble. This region is famous for it, quarries cutting deep into the land, white stone surfacing in buildings, walls, and even dust along the roads. That marble-rich geology carries directly into the vineyards, influencing drainage, temperature, and the way vines struggle and adapt.

The wines reflected that tension beautifully. There was structure here, but also a certain brightness, a lift that felt mineral rather than acidic, as if the land itself were holding the wines upright. Nothing felt heavy or indulgent, these wines were elegant in their balance.

Monte Branco’s approach mirrored its setting, small production, careful decisions, and a refusal to overwork what the land already provided. Tasting there reinforced something Alentejo kept repeating, that when soil is distinctive enough, the best choice is often to step back and let it speak.

Herdade São Miguel (Redondo)

Herdade São Miguel felt welcoming in the truest sense of the word.

Set near Redondo, the estate carries a warmth that isn’t manufactured and from the vineyards to the table, everything felt oriented toward sharing rather than display. The wines mirrored that generosity, they were super expressive, approachable, and grounded, built to be enjoyed in company rather than contemplated in isolation.

The winemaking here leans into balance again. The whole region really was excellent at balancing the heat and acid in their wines. Ripeness is embraced without tipping into excess, and tannin is present but soft-edged and plsuhy, allowing the wines to move easily across the palate. These are wines that you could enjoy on a daily basis and still enjoy the magic of.

Our final dinner took place here, and that context mattered. After days of tasting and travel, São Miguel proved, yet again, that wine, when it’s handled with care, belongs at the center of a table, not above it. Conversation widened and our laughter lingered, nothing needed to be rushed or explained.

Leaving that night, I realized something simple, Alentejo had never asked me to understand it, only to stay long enough to feel it. This will forever be one of my most favorite wine trips.

Other Reads You Might Enjoy:

The Art of the Hangover Cure: What Science, Culture, and This Sommelier Say to Do

A Sommelier’s Perfect Finger Lakes Trip: Wineries, Waterfalls, and Unforgettable Bites

The Future Is Light: Penfolds Bets Big on No- and Low-Alcohol Wine

Fermented Futures: The Rise of Alt-Alcohols (Kvass, Tepache, Makgeolli)

An Ode to Yeast: The Microscopic Magician Behind Every Glass of Wine

How to Buy Great Wine at a Regular Grocery Store (Without Getting Scammed)

Wine Closures: Screw Cap vs. Cork vs. Glass (and Why It Actually Matters)