What Really Happens When You Get Stung by a Bee

I must be in a buggy-mood because yesterday I wrote about phylloxera and then got stung by a yellowjacket while I waited for my car to be serviced. And in true Michele-fashion, I decided to write about it.

It happened fast, too fast for my brain to even process before my body flinched. It was a sting, a flash of pain, then a pulse of heat.

It’s one of nature’s smallest moments of violence, and yet inside that annoying second is an entire microscopic war with chemicals, nerves, instincts, and a little bit of heartbreak too.

Because when you’re stung by a honeybee, she dies for it.

But when you’re stung by a yellowjacket, well, that’s just the beginning.

The Sting

The moment the stinger touches your skin, it’s not just an accidental little prick, it’s precision engineering at its most deadly (am I exaggerating? Maybe, but I’m still bitter toward that yellowjacket).

A honeybee’s stinger is barbed, like a harpoon. Once it punctures flesh, it anchors into place, continuing to pump venom in even as the bee pulls away. She doesn’t survive that act of defense, sadly for her. Her abdomen tears apart, leaving behind her venom sac and stinger, still pulsing like a tiny biological machine. Honeybees tend to sting when they feel threatened or their hives is in danger.

A yellowjacket, however, plays by crueler rules and doesn’t care if you’re minding your own business waiting for the new tires to be put on your car.

Its stinger is smooth and super unfortunately, reusable, designed for multiple attacks (joy). They can sting again and again, injecting venom with each strike. Yellowjackets aren’t interested in dying for the colony (not really the martyrs of the insect world); they’re interested in making sure you leave their space, and fast.

The Chemistry of a Sting

Venom is nature’s deadly game written into molecules.

Bee venom (known as apitoxin) contains melittin, a peptide that breaks down cell membranes, causing pain and inflammation. It’s accompanied by phospholipase A2 and hyaluronidase, enzymes that spread the venom deeper through your tissues.

It’s not just chemical chaos (although its plenty of that too), it’s biological strategy, evolved to defend the hive.

If you ever get stung by a honeybee, scrape the stinger out quickly with a fingernail or credit card, don’t pinch it. Pinching squeezes more venom into your skin, that little pulsing sac is still alive for a moment, doing what evolution designed it to do.

Yellowjackets, meanwhile, wield a sharper kind of cruelty, because of course they do. Their venom contains acetylcholine, which directly stimulates your pain receptors. It’s why yellowjacket stings burn more intensely and swell more aggressively. Which I can attest to, first-hand after that stupid bee got me.

Their venom also includes a different enzyme cocktail, one that’s designed for offense, not defense.

That’s the unsettling truth that might make you want to squish a yellowjacket and be sad for a honeybee who sting in sacrifice. Yellowjackets sting for sport.

The Body’s Counterattack

Within moments, your immune system recognizes the invasion.

Mast cells near the sting site release histamine, widening blood vessels so white blood cells can flood in. That’s why the area turns red and warm almost immediately.

Swelling is your body’s way of trying to isolating the venom, as inflammation is containment from the rest of your body.

If your immune system overreacts, that’s when hives spread, breathing tightens, and anaphylaxis begins.

It’s not the venom itself that kills some people, it’s their body’s panicked overdrive being unsure of what to do.

For most of us, the reaction stays local with that annoying pain, itch, and heat. A reminder that we’re soft creatures in a sharp world. It also makes me grateful those giant bugs died out before the dinosaurs.

When the Buzz Becomes Dangerous

About 3% of adults are allergic to insect stings, and for them, what starts as a tingle can spiral into something life-threatening.

Anaphylaxis can cause airway constriction, a drop in blood pressure, and dizziness within minutes.

If it happens, there’s only one word that matters: EpiPen. I dearly hope everyone has one near enough in case of the unthinkable.

For others, reactions can look more mild but still feel miserable: fatigue, headache, and mild nausea. The body processing what it perceives as a tiny toxin storm is in fact a tiny little storm.

Interestingly enough, the location of the sting also matters a little bit. On the arm or leg, you’ll most likely get swelling and redness.

On the face, near the eye or lip, the swelling can look alarming but often isn’t dangerous. Of course mine was on the neck, so cue the severe swelling that makes me look lumpy and strange for a few days.

And multiple stings, especially from yellowjackets, can overwhelm even a healthy immune system.

Luckily for me, I panicked and swatted the yellowjacket into my shirt. Now, it wasn’t a nice feeling with it parading and marching across my torso for a few MINUTES before I was able to get it out, but the internet says I disoriented the bee and probably damaged its little body in the process, making it unable to sting me more than once.

Why Yellowjackets Are So Much Meaner

Let’s be honest, honeybees are gentle souls in comparison to the mean yellowjacket that got me.

Yellowjackets are carnivorous, territorial, and short-tempered. They also like to seem to sting people who are minding their own business at Mavis discount tires who are already stressed about the price of the tires and wondering how they’re going to financially recover from them. They’re wasps, not bees, and they build their nests in the ground or in crevices, places we accidentally disturb without meaning to or even noticing.

Unlike bees, they don’t lose their stingers and can keep jabbing until they’re satisfied you’ve learned your lesson. Hateful little buggers.

Their venom is designed for hunting, not defending, and that difference changes everything about the pain you feel.

Healing and Aftercare

If you’re stung remove the stinger immediately (for honeybees). Apply a cold compress to reduce swelling, and take an antihistamine to ease any annoying itching. A paste of baking soda and water can help neutralize any acidity that’s left behind, and for the love of god, avoid scratching, it just spreads irritation.

Most stings heal within a few days, but some can linger longer, especially for those with sensitive skin or repeated exposure. My money is on this sting I got will last about a week.

And if you ever have trouble breathing, dizziness, or swelling beyond the sting site, that’s not the time for home remedies. That’s the time to call 911.

Mine actually caused an annoying little delayed response and when I slept last night I developed some hives and hot flashes that disturbed my rest. The interwebs told me it’s just my body processing out all the venom and I’m most likely sensitive to it. Good thing I already carry around an EpiPen.

Pain and Purpose

There’s a strange symmetry in it, the way nature pairs beauty with danger.

But nature is also famous for doing this: think beautiful bright red colors are typically poisonous, and what rose ever bloomed without thorns?

Bees give us honey, flowers, and the shimmer of pollination, yet in defending that beauty, they sometimes hurt us.

Yellowjackets, fierce and unromantic little a-holes, are scavengers and cleaners, but I guess they keep ecosystems balanced, too, even if they seem like yesterday’s villains.

A little reminder that nature’s elegance is never free, and that even the smallest creatures can leave a mark far larger than their size.

Even at the discount tire place.

Related Reads You Might Enjoy:

The Healing Science of Hugging: Why Touch Might Be the Most Powerful Medicine of All

The Whispering Cure: Limewashed Trees, Natural Pesticides, and the Disappearing World of Insects

Why Your Houseplants Might Be Gossiping (and Other Strange Plant Behaviors)

The Secret Life of Soil: Why Healthy Dirt Might Be Smarter Than You Think

The Day the Ocean Whispered Less: When Blue Whales Began to Go Silent

The Hidden Violence in Our Food Chain (Even When It’s Vegan)

The Wild Side of AI: From Resurrecting Direwolves to Talking with Plants

The Plants That Predict Earthquakes: Is Nature Trying to Warn Us?

Why Do We See Faces in Everything? The Science of Pareidolia

How the Brain Reacts to Light Pollution: What Happens When We Forget the Night

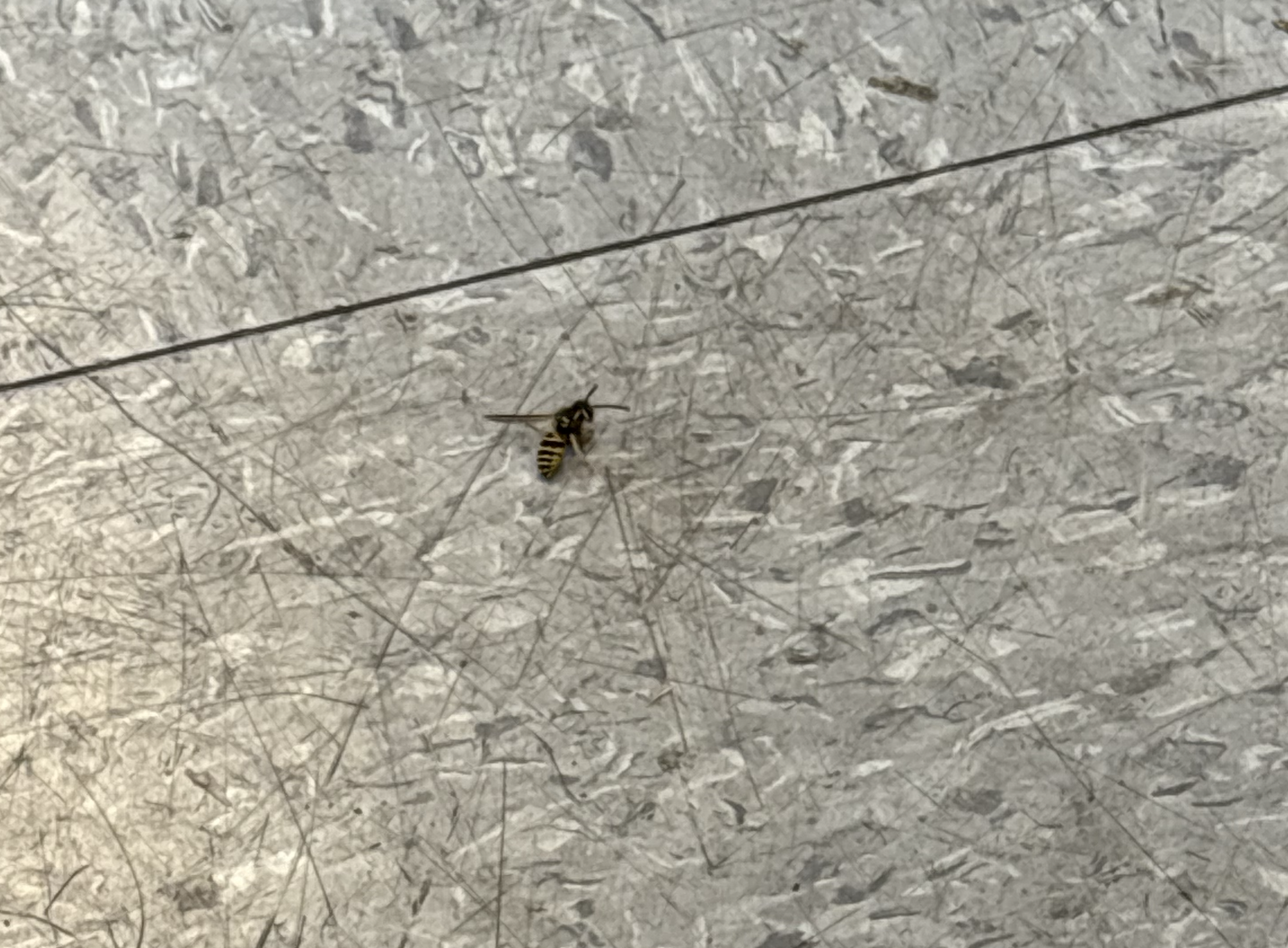

Here’s a picture of the a-hole who stung me yesterday, in case you were curious. And yes, he did die within the two hours I was waiting there.