The Alchemy of Time: The Science Behind How Wine Ages

Wine with age on it is one of the best pleasures the universe has ever bestowed upon us. Of course, I’m a sommelier, so that might be a slightly biased opinion, but here we are.

There’s a whisper of truth and time in every bottle of wine. A quiet hum of years gone by if you will, of the seasons layered like sediment at the bottom of a bottle, and of the sun filtering through forgotten vineyards, left to grow wild through time.

When we uncork a well-aged wine (carefully so we don’t snap the cork), we aren't just opening a drink to throw back like water, no, we're opening a literal time capsule, a vessel of chemistry mixed with climate, and stitched together with care. Aging wine is not just about waiting for time to pass, it's about transformation, a delicate alchemy where molecules dance slowly in dark musky cellars.

The Birth of Wine’s Potential

Every wine begins as a symphony of sugars, acids, tannins, phenolics, and volatile compounds, which is just an aromatic blueprint, its potential lying dormant in wait.

Freshly bottled wine can be vibrant and assertive as most youthful things are, but like a bold young person, it hasn’t learned the art of subtlety yet. Age teaches all of us the same lessons if we’re willing to learn.

Of course, not all wines are meant to age, and that’s the truth anyone whose opened a bottle of Sauvignon Blanc they forgot about for a decade or two learns fast. The wines that improve with time are normally structured and composed, you’ve got reds with tannins and acid, or whites with piercing minerality or sugar to balance. For the rest of them, time is a thief, stealing brightness and leaving behind a ghost.

This potential is also shaped in the vineyard via sun exposure, or grape variety, elevation, soil composition, tons of other elements whisper their intent into the wine a long time before the cork is ever sealed.

A Pinot Noir grown on a fog-kissed slope in Oregon will age differently than a sun-baked Zinfandel from Paso Robles. Terroir (the soul of the vineyard) etches its lines into the wine’s bones.

The Role of Oxygen

Oxygen is both a friend and a foe to wine in a way many love to talk about.

Expose it too much, and the wine turns brown, nutty, and tired. Just the right amount however, over years of time, and something truly magical happens. The tannins soften and harsh edges blur, aromatics evolve and shift from what we call primary flavors to tertiary ones.

This delicate flirtation begins in the barrel when the wines are still young. Oak barrels are slightly porous, allowing tiny amounts of oxygen to seep in, it’s a controlled oxidation that imparts structure and elegance. Once tossed inside a bottle, the oxygen exchange is even slower, controlled at large by the type of closure: cork allows micro-oxygenation; screw caps far less so.

With oxygen, phenolic compounds polymerize…tiny molecular structures link arms, forming longer chains and deeper companionship. Okay, maybe my personification went too far there, I’m not sure if they enjoy each others company or just tolerate it, but either way, they link up. These heavier molecules then drop out of suspension, forming the sediment that collects at the bottom of an aged bottle. The wine becomes silkier, its bitterness recedes, and its aromas blossom into leather, tobacco, dried fruit like figs, and violets.

Oxygen also creates acetaldehyde, which is a compound responsible for the bruised apple aroma often found in sherries and aged white Burgundies. While it might seem strange to seek out flavors of oxidation, when balanced properly, they add elegance and depth, a beautiful contrast to the fruit that once shouted.

Acids and Esters

Acidity in wine acts as a backbone.

As it ages, malic acid (think tart apples) may transform into the softer lactic acid (think milk), especially if the wine undergoes malolactic fermentation. This evolution adds roundness to the texture and layers to the flavor. Think about the way different percentages of milk feel in your mouth. 2% feels incredibly different than whole milk versus heavy cream.

Meanwhile, volatile aroma compounds (called esters) interact and evolve while they’re waiting for time to pass. Fruity esters fade and complex ones form. Primary aromas of strawberry or citrus often give way to secondary notes of honey, nuts, or forest floor. The wine begins to speak in paragraphs instead of exclamations, deepening in complexity.

Then there’s tertiary aroma development I mentioned earlier…these are the truly poetic scents that speak to my soul, think: old library books, autumn leaves, saddle leather, dried figs, lanolin, dried roses, and forest after rain.

These aren’t the result of fermentation normally, they’re time’s slow signature, stamped and marked moving forward on any wine.

Red vs. White

Red wines age with the help of tannins, which act as natural preservatives. In a young wine, tannins are like you tongue has tried to have a handshake with sandpaper. Over time though, they mellow, rounding out the mouthfeel and allowing fruit and earth tones to shine.

Age-worthy reds include (but are not limited to!) Bordeaux blends, Barolos, Brunellos, and certain Syrahs and Cabernets.

White wines age through their acidity and, in some cases, sugar. Rieslings, Sauternes, and vintage Champagnes can age for decades, their acidity preserving them while they evolve into expressions of beeswax, petrol, and marzipan. Even some white Burgundies, with their creamy texture and minerality, improve with time, developing into opulent, hazelnut-laced marvels.

Sparkling wines offer a fascinating side story as well: as they age, bubbles soften, and yeasty autolytic notes (think toasted brioche and almond cream) begin to bloom. Well-aged Champagne becomes a feast for the senses, elegant and effervescent with echoes of its bubbly youth. When I was gluten-free for years I would seek out old Champagne to drink to remind myself what freshly baked bread tasted like (true story).

Of course, time alone can’t work its magic without the right conditions. Temperature is critical: ideally 55°F (13°C), stable and cool. Fluctuations accelerate chemical reactions, aging wine prematurely and unevenly. Light is the enemy of all wine; it penetrates the bottle, spurring unwanted reactions. That’s why most wines built for aging use darker colored glass bottles to try to prevent the light from shining through.

Humidity matters too more than you’d think. Too dry, and corks shrink, letting oxygen in too fast, and ruining your wine. Too damp, and labels peel while mold creeps in (I’ve had this issue more than once before, it sucks when your labels get ruined because of it). The perfect cellar is dark, slightly humid, and steady as a heartbeat. Of course, bottles should always be stored sideways as well, so the wine touches the cork and keeps it moist.

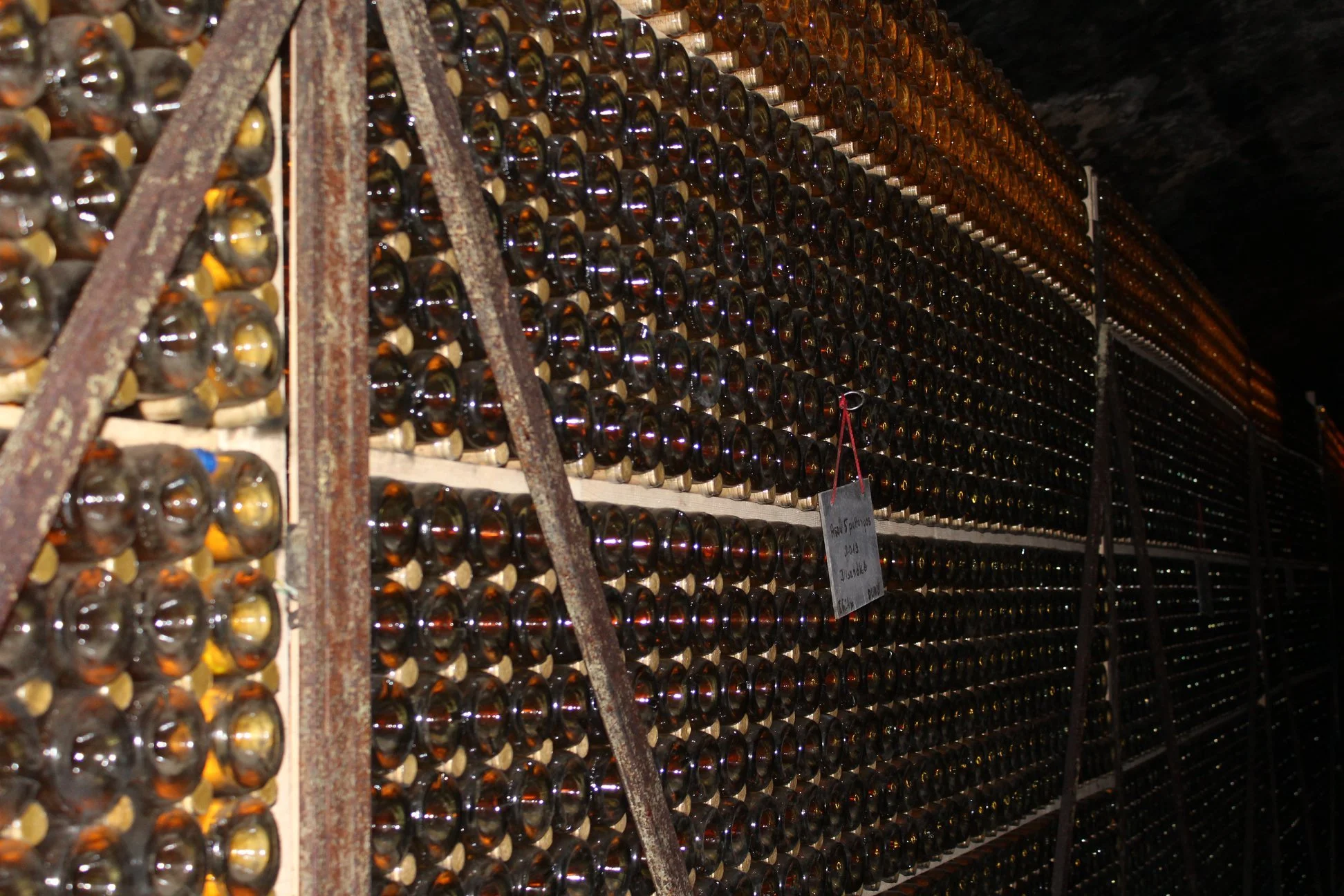

Collectors often invest in high-tech wine fridges or even build subterranean cellars. Whether your stash is a few treasured bottles or an expansive vintage library, the principles remain the same, protect your wine from the chaos of the world so it can age gracefully in silence.

One day, when my blog finally catches up with my ambition, I’ll be building a cellar in some cave or such with a natural water source trickling through to regulate the humidity. That’s my dream, anyway.

The Chemistry of Patience

Wine’s aging is driven by reactions that happen at literal glacial speeds that isn’t built for the impatience of today’s society. Anthocyanins (color compounds) fade, leaving reds brick-toned or tawny. Tannins polymerize, growing larger and softer as aldehydes accumulate, lending notes of bruised apple or nuts.

These changes are imperceptible day to day, but truly profound over years. Wine aging is a time sculpture, a slow, irreversible carving of aroma, color, and taste.

Interestingly enough, different bottle sizes age differently. Magnums, with their larger volume-to-air ratio, often age more slowly and gracefully than standard bottles. That’s why collectors often prefer large formats for long-term cellaring if you noticed before.

Some wines are born perfect, while others grow into it. Aging allows wine to reveal its true soul, to show us what it’s capable of beyond the noise of youth…it teaches us patience. Aged wine rewards us with something we couldn’t know we needed.

A bottle opened too soon may taste sharp, or unformed, sometimes they have a feeling of being scattered.

The same bottle, given enough time, may pour out in poetry. Aging teaches us about restraint, and about faith. It’s not just chemistry, it’s philosophy: a belief that waiting has value. That the best things often come when we least expect them, long after we’ve stopped checking the clock.

In the silence of a cellar, wine is dreaming, and when we drink it, we wake those dreams.

Related Reads

The Art of the Hangover Cure: What Science, Culture, and This Sommelier Say to Do

A Sommelier’s Perfect Finger Lakes Trip: Wineries, Waterfalls, and Unforgettable Bites

The Future Is Light: Penfolds Bets Big on No- and Low-Alcohol Wine

Fermented Futures: The Rise of Alt-Alcohols (Kvass, Tepache, Makgeolli)

An Ode to Yeast: The Microscopic Magician Behind Every Glass of Wine

How to Buy Great Wine at a Regular Grocery Store (Without Getting Scammed)

Wine Closures: Screw Cap vs. Cork vs. Glass (and Why It Actually Matters)

Upgrade your home cellar with the Ivation 33 Bottle Dual Zone Wine Cooler, designed for ideal humidity and temperature control. Quiet, sleek, and built to age your wines as they deserve.

Let the young wines sing, but let the old ones speak too, because what they have to say isn’t louder…it’s deeper. In the hushed amber glow of a glass raised to your lips, that depth is all we need to remember what time can do when we let it.

Please enjoy the image of my dream cellar.