The Frozen Whisper of a Young Star: Water, Origins, and the Cosmic Nursery of HD 181327

In the beginning, there was ice. The roaring fire came later with the brilliant blaze of suns.

But ice was the start of everything, nice and silent, slow, and ancient.

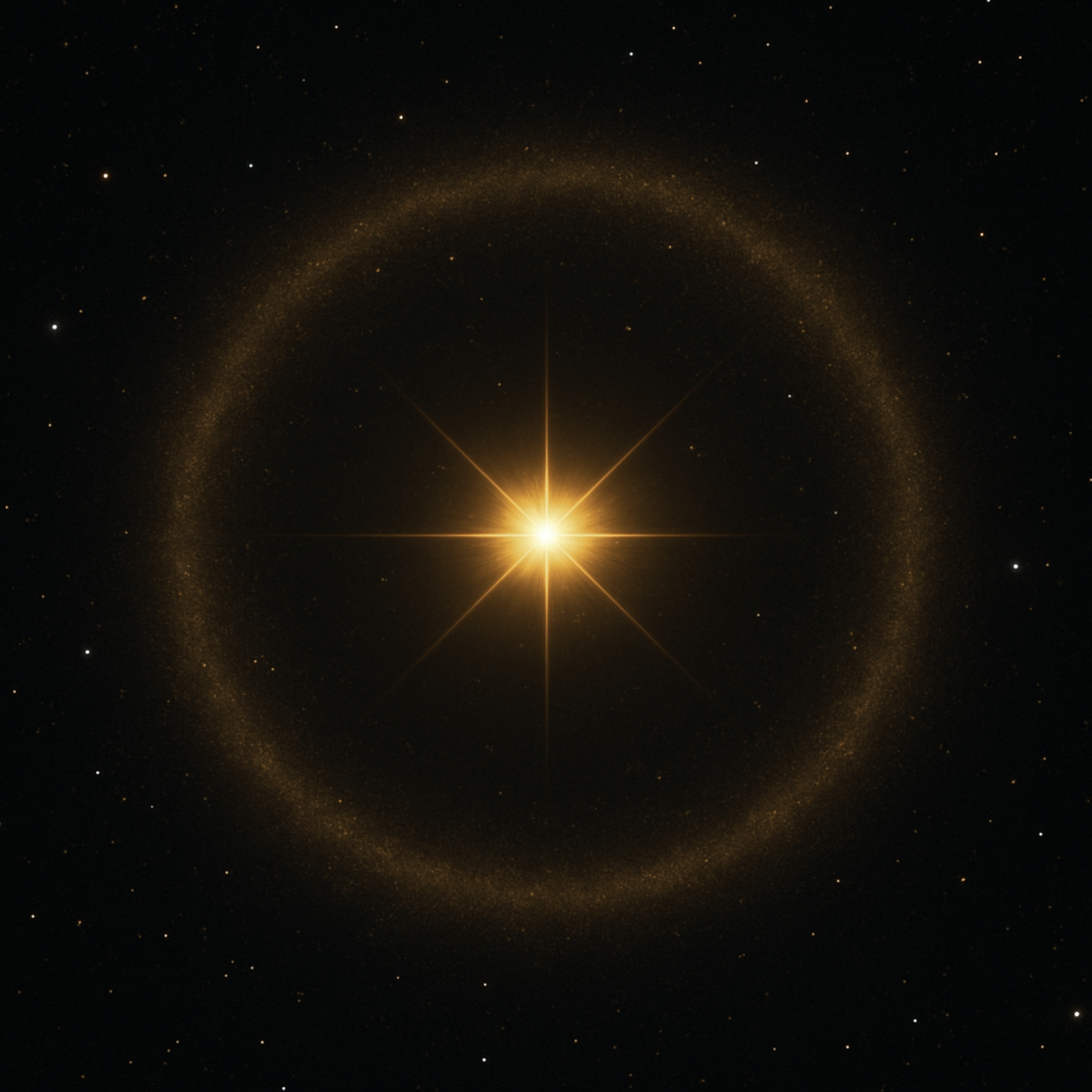

Far, far, far beyond the echo of our own solar nursery, in the constellation of Telescopium (dude, I didn’t name it), a young sunlike star named HD 181327 swirls quietly in the velvet dark.

It’s only about 155 light-years from Earth, which isn’t that far believe it or not, but its story spans eons. Now, thanks to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), we know this story was written, at least in part, in frozen water.

Ice hanging out around a young star in the dust and chaos of a planetary nursery, and with it, the musings of a question: did our story begin this way too?

A Celestial Snapshot of Youth

HD 181327 is not an ancient elder. This star is young, only about 23 million years old (just about the age I feel after working a double), still in the thick of forming its little family of planets. Unlike baby photos here on Earth that every mom ever seems to capture, this one wasn’t captured in soft lighting and sepia tones.

It was photographed in infrared, deep and rich, by the JWST, whose mirrors drink in some of those wavelengths invisible to the human eye. What scientists saw was truly extraordinary too.

A debris disk around the star, a swirling band of dust, rock, gas, and icy particles, glimmering faintly with the unmistakable chemical signature of frozen water. That’s right, not steam, or sloshing liquid, but magical ice. (Let it gooo, let it gooo.)

The same kind of ice that coats comets, not the kind that shoots out of Elsa’s hands. This kind of ice might’ve delivered Earth's oceans to us.

Suddenly, our own planetary origin story feels a tiny bit less like a miracle and more like a melody played again, elsewhere in the galaxy. The universe’s favorite track of life.

Cosmic Water Delivery Service

Earth, as you may have heard (or swam), is a watery happy miracle. Oceans cradle continents, clouds rise and fall in rhythmic tides, and we ourselves are mostly water wearing skin. That’s definitely going on my resume, water wearing skin sounds bad-ass.

…but where did it come from?

For decades, scientists have debated whether Earth formed with its water, or whether icy comets and asteroids bombarded the dry rock and delivered the gift of life later. The answer could very well be both. But the discovery at HD 181327 strengthens the theory that young planetary systems naturally form with ice in their midst, and possibly on their surfaces already!

This isn’t just theory anymore, it’s evidence found in stardust data. That means that planets born in the debris disks of stars like HD 181327 could be born already seeded with the elements of life, not completely barren like we once thought.

Water is waaay more than hydration after all, it’s life potential.

To understand what the James Webb Space Telescope saw, you might have to step outside yourself for a moment and float around into the dark, where a young star spins with all the defiant heat of something newly born. Around a baby star you won’t find order, but entropy. A disc of dust and debris, wild and unformed, swirls like cosmic confetti, sort of like how seagulls circle you on the boardwalk after buying fries.

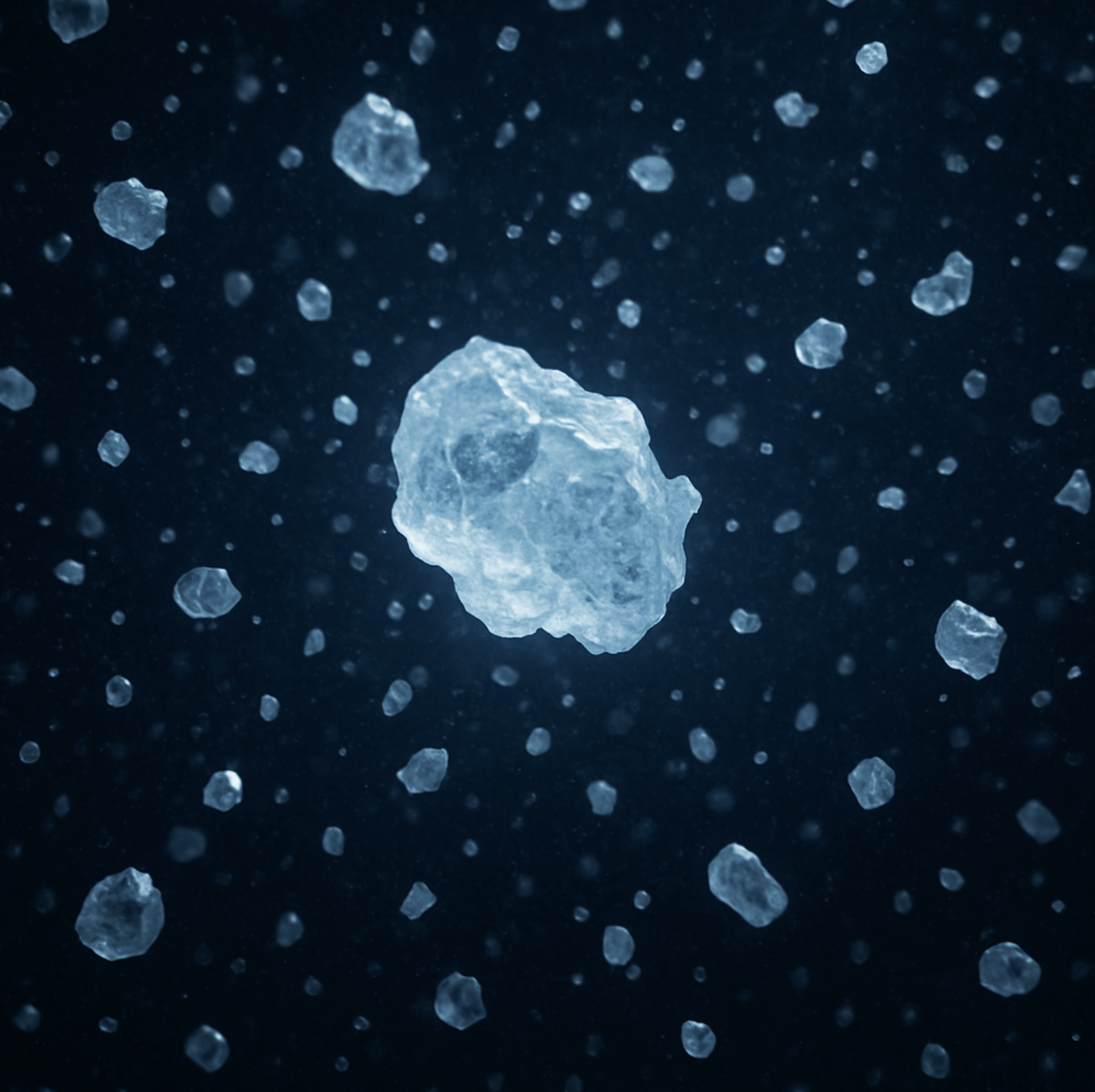

Closer in of course, the heat is brutal. When you venture farther out though…and farther still…everything changes. The temperature drops and motion slows. There, in the quiet outer reaches, water turns to ice, tiny frozen grains no bigger than sand glint around like secrets in the dark.

This distant region is eerily familiar…a mirror of our own solar system’s Kuiper Belt, where Pluto drifts and comets are stitched together from frost and rock. It’s here that planets begin their long sculpting, drawn from disorder like sculpture from stone. In this frigid nursery, JWST found something beautiful: frozen water. A sign that volatile molecules (ingredients for oceans, for air, for life) are scattered generously across the stars.

It’s a quiet discovery, but a loud one, too, because if water is there, then life…someday, somewhere…might be too.

Other Reads to Explore:

Move Your Body, Grow Your Brain: The Mind-Blowing Science of Exercise and Neuron Growth

The Invisible Symphony: How the Universe Flickers Through Our Lives Without Us Knowing

Through the Shadow of a Giant: What We Learned from Uranus Passing a Star

The Moon’s Mysterious Reach: Everything It Touches, from Tides to Werewolves

The Great Attractor: The Mysterious Force Dragging Our Galaxy Toward the Unknown

When the Light Becomes Too Bright: How a Quasar Silenced the Sky

The Shattered Planet That Lives On: What Vesta Tells Us About Cosmic Ruins

The Light That Shouldn’t Exist: Discovering Stars in the Darkest Corners

Why Gold Is Born in the Stars: The Alchemy of Colliding Neutron Stars

The Ice Is Not Alone

It wasn’t just the water that stirred the scientists either, it was the dust, too. Silicates, to be exact, tiny mineral fragments, like the ones that once built the bones of Earth’s crust.

There they were, drifting through the cold, silent dark raw ingredients for something solid, something that might last.

I like to think of it more like a frozen cosmic stew, thick with icy grains and glinting crystals. Rock and water, suspended in the void, waiting for gravity to do what it always does, gather then press and sculpt.

Slowly and silently and with enough time thrown into the mix, chaos begins to coalesce. Dust becomes pebbles, and when enough time passes, pebbles could become worlds.

Maybe, one of those worlds will bloom with oceans and storms. Or with something that learns to walk upright, tilt its head to the stars, and ask, “where did we come from?”

What This Means for the Search for Life

It’s tempting to believe life is a fluke, a rare little spark in a cold, indifferent universe, but discoveries like this hint at something different…something that screams maybe life isn’t rare. Maybe it’s written into the recipe, just add water, and wait, because water isn’t scarce.

Ice hides in shadowed craters, clings to comets, and drifts through protoplanetary discs like glitter. Now, even in the earliest chapters of a star’s story, at the very moment planets begin to form, we see water woven into the dust, like memory. HD 181327 is just one voice in a choir, there are literally countless others. Thousands, maybe millions, of stars stitching together new worlds from the same frozen threads, and with every discovery, the truth presses closer. Life might not be an accident.

The universe could be fluent in water. Somewhere, far off, another world is bursting with a history we’ll someday recognize as part of our own.

The star HD 181327 lies in the southern constellation Telescopium. It’s not visible to northern skywatchers, but for those in southern latitudes, it’s a quiet patch of sky between Sagittarius and Pavo. Even if you can’t see it, know this, the next time you look at the stars, you’re looking at oceans in the making, icy promises in orbit, and futures forming in frost.

Want to See the Stars Like Never Before?

If you're dreaming of spotting icy comets, nebulae, or even the faintest hint of a stellar nursery from your backyard, you’ll need the right gear. I recommend this: Celestron StarSense Explorer LT 114AZ Smartphone App-Enabled Telescope

It’s user-friendly, affordable, and perfect for curious stargazers who want to find their way without fumbling through star charts.

Star Dust

We like to imagine life beginning with fire…with a spark, or a flash, some sort of dramatic ignition, but sometimes, it starts in the quiet. In the cold hush of space where grains of ice drift, circling a newborn star not yet done learning how to shine.

HD 181327 is young, still stretching into existence. And yet, it carries something old…something familiar, because in that swirling disc of dust and frost, we see echoes of where we came from, and even hints of where life might go next.

Yes, we’re stardust, but we’re also meltwater, little trickles from ancient snow. The gentle seep of cosmic beginnings all begins in places like this…in the frostbitten dark, before the warmth arrives.